Summary of the FairSearch complaint to the EU against Google

A summary of the complaint submitted by FairSearch against Google

in relation to Google’s Android Operating System (“OS”)

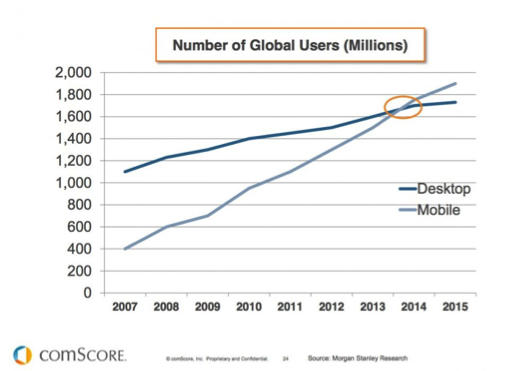

Access through mobile devices is rapidly becoming the primary mode of internet consumption. It is expected that global mobile data usage will increase 18-fold from 2011 to 2016. Mobile Internet traffic now accounts for over 17% of all Internet traffic, and more than 50% of all local searches are already done from a mobile device.

Mobile applications (“apps“) are becoming increasingly popular as the primary means of accessing Internet content and services on mobile platforms in view of the limitations on text input and screen size and the convenience of touch-based interfaces. Recently, apps have even overtaken desktop computers in relation to Internet consumption in the U.S.[1]

Mobile advertising is rapidly growing. The growth of mobile Internet consumption reflects changes of usage patterns of media consumption. Users are relying more and more on mobile devices to access content that is or was primarily delivered through traditional media: users watch TV content, listen to radio as podcast, read newspapers and magazines on their mobile devices. In many countries, smartphones have become the most viewed medium. Moreover, the vast majority of owners of smart devices use them in parallel with other traditional media, in particular while watching TV. Due to the mobile devices’ success in captivating users’ attention and the possibilities they offer in relation to customer engagement, mobile advertising is growing dramatically.

Google’s profitability is based on its dominant position in search and online advertising. Google holds a dominant position in the market for algorithmic Internet search with more that 85% of desktop Internet searches being made using the Google search bar in 2013.[2] Google also offers AdWords, a search online advertising service that places a copy of an ad on the website displaying the search results for a particular query, and AdSense, a non-search contextual online advertising service that places a copy of an ad on a website that is part of the Google Network. Thanks to its dominance on the market for Internet search, Google has developed into one of the most profitable Internet businesses based exclusively on revenues from online advertising. In 2005, Google generated USD 6 billion in revenues exclusively from desktop advertising, and had no mobile business to speak of. It had already firmly established itself as the globally dominant search engine and search ad provider, and was rapidly expanding its non-search advertising business as well.

The rise of mobile platforms and mobile advertising represented a threat to Google’s traditionally PC-centric online search business and its plans to capture the online advertising market. When the adoption of mobile platforms started to grow in earnest, the emergence of a new online advertising platform (not yet dominated by anyone) appeared to Google’s rivals and new entrants as an opportunity to challenge Google’s dominance in the search and online advertising markets. Indeed, the new possibilities of collecting user data thanks to apps created an opportunity to offer targeted advertising services independently of Google. Entering successfully the mobile advertising market would then in turn provide the successful companies with a foothold to develop expertise and scale to challenge Google’s dominance in the desktop advertising market.

To stave off this potential threat, protect its search monopoly, and increase its share in online advertising more generally, Google set out to establish itself as the ubiquitous licensable mobile OS provider. Google set out to establish itself as the predominant provider of mobile operating systems to OEMs by acquiring the Android OS and licensing it at no cost to OEMs. The established mobile phone OEMs did not have a strong tradition of developing software, and in the face of the emergence of software-centric smartphones needed smartphone OS software. They were all too keen to license an immediately available, free, open source smartphone OS from Google.

In order to ensure the broadest possible adoption of Android, Google implemented a “bait and switch” strategy. Upon launch, it heavily marketed Android to OEMs and developers as a community driven, open source and truly open alternative to proprietary systems from other vendors, which did not come with the control restrictions of these other vendors, and could be easily adapted and improved based on open source principles, resulting in vibrant competition and innovation. In reality, however, Google quickly started providing two different versions of Android: one open source version called Android Open Source Project (“AOSP“), which it has progressively starved of advance functionality, and another, which we will call “Google Android,” which is the version Google actually provides to OEMs, and which it has progressively closed down. Google has done so by including in Google Android a proprietary API layer called Google Play Services in 2012. Since its introduction, most of the significant improvements to the Android OS were implemented in this Play Services layer rather than in the OS itself. The Play Services layer is proprietary to Google and not open source: it is distributed via Google Play Store, and is thus not part of AOSP or any forks based on AOSP such as Amazon Fire OS (as Google Play Store is available only for devices that are subject to the Mobile Application Distribution Agreement (“MADA“) and that thus run Google Android). Play services is required for all main Google applications and related services, including YouTube, Gmail, Google Maps, and the Play Store, the principal repository of Android applications, which are critical to the usefulness of the Android OS. At the same time, developers are encouraged (and in some cases, required)[3] to use the Play Services APIs, meaning that more and more apps become dependent on Google Android and will not work or are not easily adaptable to run on AOSP versions. Moreover, Google updates the Android OS by updating the Play Services layer thereof which means that the updates of the Android OS only benefit Google Android and not AOSP. Further handicapping AOSP, Google Android is generally released well before corresponding AOSP versions, which have trailed Google Android by several months.

To prevent OEMs from competing with Google Android on the basis of an alternative implementation of Android, Google makes the use of any of its main apps, including Google Play Store, subject to the OEMs joining the Open Handset Alliance (“OHA“). Whilst joining the OHA is free, its members must sign the Anti-Fragmentation Agreement (“AFA“), which requires them not to create or promote any third party software development kit (“SDK“) derived from Android, or derived from Android Compatible Devices. Given that the most important OEMs, several app developers, chip manufacturers and some MNOs are members of the OHA, a fork of Android is unlikely to become successful one day. Indeed, if an OEM distributes a product including Google Android, it is prohibited from also distributing devices reliant on its own OS based on Android (AOSP): Google has been successful at forcing Acer to cancel the launch of its smartphone running on Aliyun (an Android fork) and Asus to cancel its Transformer Book Duet TD300, which could boot both Android and Windows 8.

OEMs who thought they were investing in the development of an open source product that would allow them to provide differentiated offerings by licensing Google Android are now effectively locked into Google Android and Google Play Services, and the applications barrier that relies on Play Services. Developers of competing AOSP distributions are starved of innovations and applications which rely on Play Services and the Play Store, both of which are reserved for Google Android.

Google’s grip on the only version of Android OS that is truly attractive for OEMs allows it engage into anticompetitive tying and contractual restrictions. By virtue of these practices Google is putting itself in a position that enables it to successfully foreclose competition on the markets it is active in, in particular those for various apps and related online services and mobile advertising.

Google ties mobile apps and services together for distribution by OEMs on its Android platform. To protect and expand its position in online advertising, Google needs to accumulate user data. The operating system provides a means to do so, but only to a degree (e.g., device-specific information, mobile network information including phone number and location). The richest data is acquired through apps and related services installed on the OS. Apps (e.g., search apps, map apps) enable apps providers to collect much richer data disclosing, e.g., user preferences, than the data resulting from OS usage. In addition, apps can also provide a source of third party advertising revenue through in-app advertising. Thus, even if Google controls the principle licensable mobile OS, it would continue to face threats to its online advertising position from popular apps providers and miss out on mobile advertising growth opportunities if it did not also control the key apps distributed on its mobile platform.

Google makes sure that Google’s apps and related services are included with Android, and makes it less attractive for network operators and device manufacturers to include competing apps or services with Android. It has also been reported to delay the launch of devices on which competing services have been installed. As a result, advertisers are locked into Google and do not use Google online advertising rivals. Google also insures premium placement of Google’s applications on the Android screens, and other mechanisms for disadvantaging competing apps. Indeed, OEMs wishing to install any of the mandatory applications listed in the MADA Google has entered into with OEMs are required to install the other “mandatory” applications as well. Since end users usually expect to have some “must-have” applications, such as YouTube and Google Play, this agreement allows Google to ensure ubiquitous distribution of all the other applications that users would not necessarily install or use. Consequently, Google uses its control over the Android OS and the Play app store to promote its own apps and further restrict the availability and placement of competing apps. It further distorts competition on the market(s) for apps and related online services by delaying or withholding the availability or degrading the user experience of its most popular apps on non-Android platforms in comparison with the very same apps on the Android OS. These actions in turn strengthen the applications barrier to entry that protects Google Android from competition.

In short, Google leverages its control over Google Android to promote its apps, and ties its non-dominant apps to its dominant apps. This allows it to gather user data that it uses for advertising. Google also relies on the dominance of its apps to shelter Google Android OS from competition, thus preserving its grip over the mobile advertising platform.

Google’s anti-competitive conduct forecloses competition in the markets for (i) mobile OS (ii) various apps and related services and (iii) mobile online advertising. Helped by its anticompetitive tying, Google has now become the dominant player in the market for licensable OS for smartphones. In the third quarter of 2013, Google had over 95% of the relevant market. Even if one includes non-licensable smartphone OS, still more than 69% of smartphones sold to end users in the world are running Android. Moreover, key mobile applications, including Google Search, YouTube and Google Maps, are dominant in their markets. By tying them to its dominant OS and to its non-dominant apps, Google forecloses competition in the respective markets for various apps and related online services. It comes as no surprise that between 2011 and 2013 Google’s worldwide revenue share in the mobile advertising market increased from 38% to 53%.

Google’s anti-competitive conduct infringes 102 and 101 TFEU. Google’s conduct meets all the criteria for an antitrust infringement under the treaty.

- Google is indisputably dominant in multiple markets, including the markets for search, licensable mobile OS, as well as key apps and related online services (in particular, the Play app store for Android, YouTube and Google Maps).

- Google violates the special responsibility imposed by Article 102 by engaging in abusive tying. Rather than tying a dominant product to a non-dominant product, Google ties several services and products (some of which are dominant whereas other are not) together, in order to create a dominant ecosystem that cannot be challenged other than by competing with Google on all the relevant markets at the same time. Due to the number of Google’s services concerned and the links that Google has built between them, some of the ties are indirect. Google’s anticompetitive strategy relies on numerous ties:

- Google ties its dominant apps to its non-dominant apps: under the MADA, OEMs wishing to install one of the “mandatory” apps, which include apps that are dominant in their respective markets, must also install Google’s less popular apps[4];

- Google ties Google Play Services with Play Store: in order to benefit from updates of the Android OS, Google Play services must be installed. Google Play services are tied with Google Play, which is in turn tied to the Google Android. The only possibility to benefit from the updates of Android is to install Google Android;

- Google ties its apps and Google Android: OEMs wishing to install Google’s proprietary apps, including those that are dominant, can only do so if their devices run Google Android. Google’s apps are not available on devices running a fork.

- In addition, the effect of Google’s tying conduct is reinforced by other anticompetitive behaviours:

- Revenue sharing arrangements: Google secures effective exclusivity of its Search app on Android devices by sharing revenues from its quasi-monopoly in search with OEMs and MNOs. This conduct bears a striking resemblance to exclusivity rebates, although instead of rewarding its OEMs and MNOs with rebates on the license fee (which is impossible given that OEMs do not pay a license fee to Google for pre-installing Google’s Search app), Google rewards them with hard cash;

- Contractual restrictions on OEMs: through the Android compatibility program Google imposes several restrictions on OEMs that effectively prevent a successful appearance of Android forks. Thus, under the AFA, OEMs marketing devices with Google Android are restricted from also marketing devices that run on the Android forks. Moreover, Google’s total and unchecked control over the Compatibility Definition Document – which specifies the requirements that a device must meet to be allowed to ship with Google Android – enables it to restrict virtually any device from shipping with Google Android, by declaring that that device is not “Android compatible” and that shipping it would be in breach of the AFA. As being found in breach of the AFA may result in the OEM losing access to the entire universe of Google apps, these contractual restrictions imposed on OEMs eliminate the incentive for OEMs to compete with Google either directly (by developing an Android fork) or indirectly (by supporting such a fork);

- Restrictions imposed on app developers: Google restricts developers’ ability to port their Google Android apps to AOSP-based forks by making its APIs incompatible with Android forks, even though for certain functionalities (g., in-app payments) alternative APIs are not allowed for apps distributed via Google Play, and by requiring that developers do not use the Android SDK to develop apps for platforms other than Google Android. As a result, providers of AOSP forks are impeded from attracting a critical mass of developers and therefore third-party apps to offer a platform that could compete with Google Android.

FairSearch believes that the effects of Google’s anticompetitive behaviour can be resolved through remedies. In particular, it is necessary that Google’s dominant Android OS and key apps are not tied to each other and to non-dominant apps to leave room for merit-based competition in these markets.

While Google claims that its success relies on merits and posits itself as an innovation champion, the truth is that one does not know whether competitors are more innovative or not, simply because Google has built barriers to entry that are virtually impossible to overcome. Indeed, as Google’s ties have created a web of interconnected services and products, to compete with Google on any of these markets a competitor would need to enter them all simultaneously. Consumers are deprived of the fruits of a sound competition based on the merits in the markets for licensable OS, for apps and related services and online advertising. It should indeed be for the consumers to decide which device, with which operating system, with which user interface, with which apps they prefer best – not for Google.

[1] http://money.cnn.com/2014/02/28/technology/mobile/mobile-apps-internet/.

[2] http://gs.statcounter.com/#desktop-search_engine-ww-monthly-201301-201312.

[3] For example, Google’s Play Store is the overwhelmingly dominant applications store for Android – no other store comes close to attaining the Play Store’s reach in terms of devices which access it, revenue generation and downloads, not in the least due to the tying practices described below. Google’s application distribution policies require that applications developers use the Google Wallet API for in-app payments, rather than any third party payment solutions. The Google Wallet API is part of Google Play Services. Any developer who wishes to develop an application based on the in-app payment/freemium model which represent a very significant portion of applications distributed for Android today, and distribute in Google Play, is required to rely on Play Services, which means the app will only run on Google Android. Even techniques such as “sideloading” will not work to make these applications available on non-Google Android platforms such as Amazon Fire, because these platforms do not have access to Play Services.

[4] The most recent available information suggests that OEMs are required to provide access to a “collection” of 13 Google apps (Google Chrome, Google Maps, Google Drive, YouTube, Gmail, Google+, Google Play Music, Google Play Movies, Google Play Books, Google Play Newsstand, Google Play Games, Google+ Photos and Google+ Hangouts). OEMs are also required to list this collection of apps in a specific order, from left to right and top to bottom within the Google icon, and also place several other Google apps, including Google Street View, Google Voice Search and Google Calendar, “no more than one level below the Home Screen.” For more information, see https://www.theinformation.com/Google-s-Confidential-Android-Contracts-Show-Rising-Requirements.